4 Lovasz-Erdős Local Lemma

What is the idea fo a local lemma? It’s a general statement in probability about when a certain probability is

non-zero.

A silly example: Say I have

independent coins. How do I prove that there exists a configuration of these coins such that everything is

heads?

Our earlier techniques don’t work on something like this: before we either started with an event that

holds with probability, or something that is close to an event that holds with high probability.

heads is

neither of these things, but obviously it exists because everything is independent.

The Local Lemma allows us to show that the probability of an event is non-zero provided we have “enough”

independence, which we make precise below.

Lemma 4.1 (Erdős-Lovasz, 70s).

Assuming that:

-

is a family of events in a probability space

-

-

,

where

is the max degree of

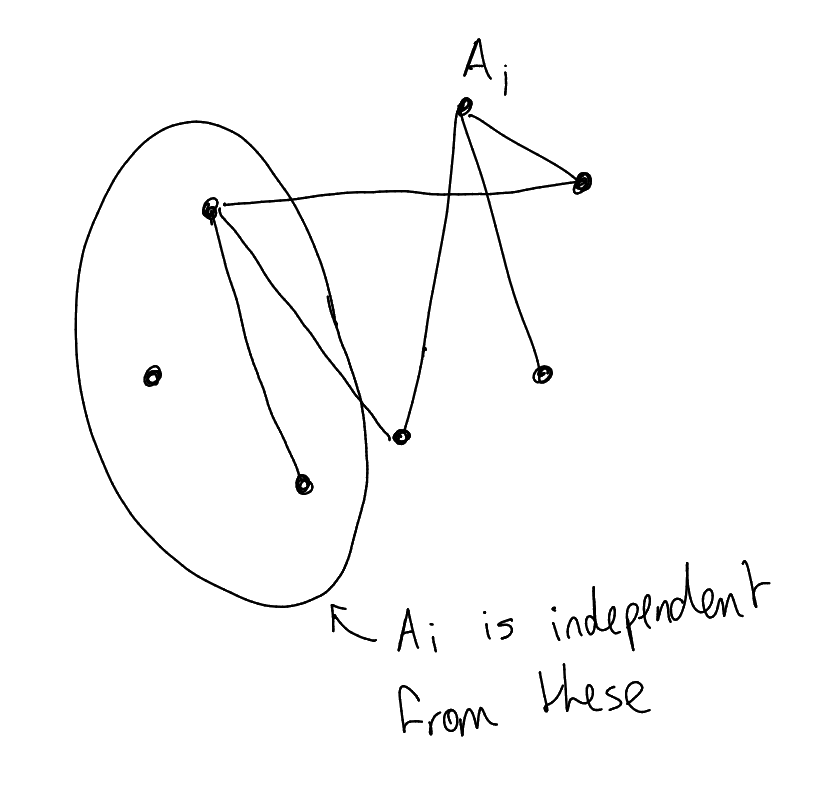

Definition 4.2 (Dependency graph).

If

is a family of events, a dependency graph

is a graph with vertex set ,

with the property that: for all ,

the event

is independent from .

Note that a family of events

can have many possible dependency graphs, but in applications there is often a particularly natural choice to

take.

Picture:

Reminder: is

independent from if

is formed by taking

intersections of ,

we have

Theorem 4.3 (Spencer).

.

Proof.

Let and let

. Choose a colouring uniformly

at random. For every ,

define the event

|

|

We clearly have .

Let be a dependency

graph on ,

where we say

if .

|

|

We now check:

|

|

This .

So the condition in Local Lemma holds for sufficiently large .

□

Remark.

This is the best known lower bound for diagonal Ramsey.

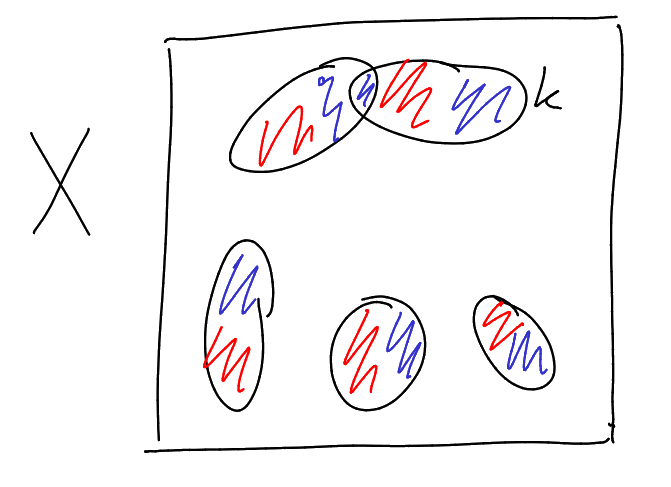

Definition 4.4 (-uniform hypergraph).

Say

is a -uniform

hypergraph on vertex set

if .

Definition 4.5 (Colourable hypergraph).

Say a hypergraph

is -colourable

if there exists

such that there is no monochromatic .

Theorem 4.6.

Assuming that:

Then is

-colourable.

Note.

This theorem has no condition on

in the assumptions. Thus, this theorem is not just picking out a high probability event out of all uniformly random

colourings: if

is large and has a reasonable number of edges, then with high probability there will be a monochromatic edge.

Proof.

We choose our colouring of the ground set

uniformly at random. For each ,

define the event

We have , so we want

. Note if we define our

dependency graph

by if

, then

Now just use the bound on

in the hypothesis. □

Remark.

Actually, our second application implies the first on

: just let

be the

-uniform

hypergraph on ,

defined by

We now move onto proving Local Lemma.

Theorem 4.7 (Lopsided Local Lemma).

Assuming that:

This is slightly more mysterious than the first form, but it can be much more useful. Specifically, if the probabilities

aren’t all the same, then this lopsided form allows us to tune the values of

more precisely than if we just use Local Lemma. We’ll see an example of this at the end of this

section.

Proof.

We use

Applying this many times, we have

We will prove that this term is

by instead proving the more general statement:

where . We prove

by induction on .

If , then

done by hypothesis.

If , then

define

|

|

Note that

Let be the events

in the intersection .

Then

If no events in the intersection, then we are already done. Otherwise, we may apply the induction hypothesis

to each term to get

|

|

Now we will see another proof of

(Theorem 3.1), in order to give some intuition as to what kind of situations are good for Local Lemma.

Roughly speaking, it works well if your events are “weakly dependent”, or there are “not too many

dependencies” among them.

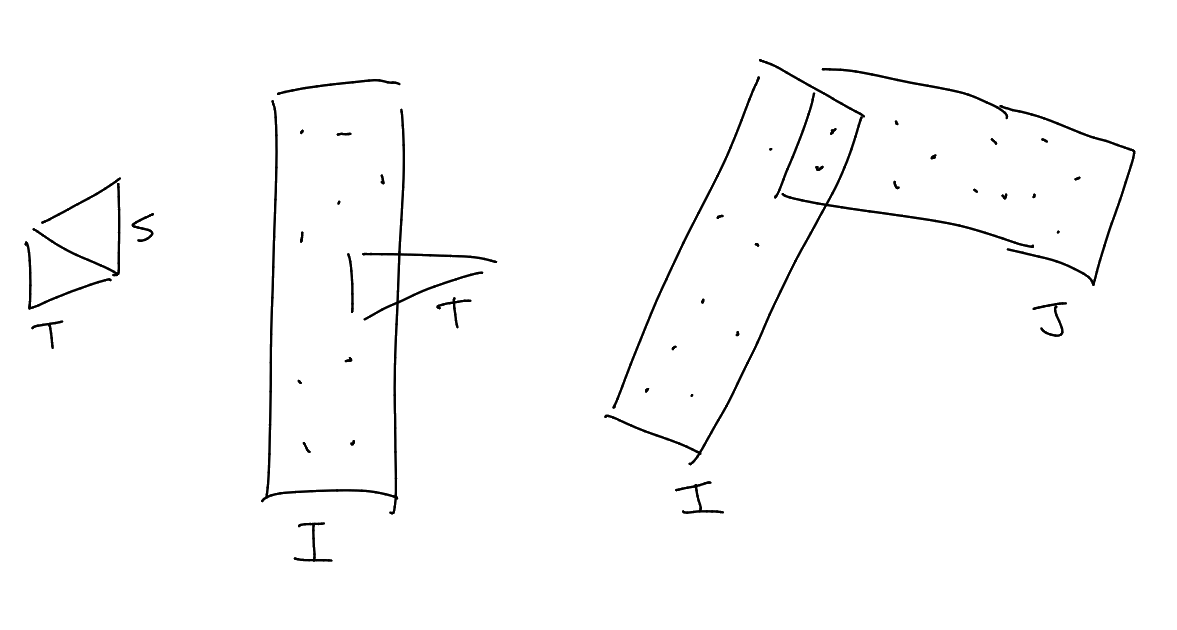

Proof of using Lopsided Local Lemma.

Recall that it is enough to show that for sufficiently large ,

there exists a triangle-free graph on

vertices with

(this was the statement of Theorem 3.2).

Set ,

and sample

where ,

with

is chosen later.

Define the events:

-

For each ,

define

-

For each ,

define

Define the dependency graph :

-

for

if .

-

for

if .

-

for

if .

Now note:

-

The event

is

to

,

.

-

The event

is

to

,

.

-

The event

is

to

,

.

-

The event

is

to

,

.

We choose

for all

(“we want to make it a bit bigger than the probability of it occuring so that we can afford the product stuff”)

and for

all .

Then

for large enough .

We have ,

so

Note

|

|

First choose

small so , and

then choose ,

then done. □