2 The Ramsey numbers

Theorem 2.1 (Erdos-Szekeres, 1935).

.

Note.

.

Corollary 2.2.

.

Idea 1: If randomly colour ,

we have

triangles :(

Idea 2: We want to bias our distribution in favour of

– colour

“red”. Say .

Sad news: if

then contains

a with high

probability. :(

Theorem 2.3 (Erdos, 1960s).

for some .

Proof idea: Sample ,

then define . For this

to work we need .

So . So

take .

Remark.

This is called the “deletion method”.

Fact (Markov). Let be a

non-negative random variable. Let .

Then

That is

for any .

Fact. For

we have

and

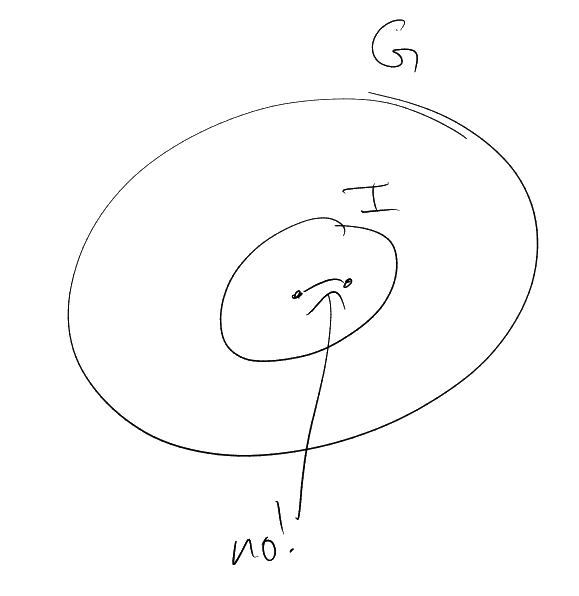

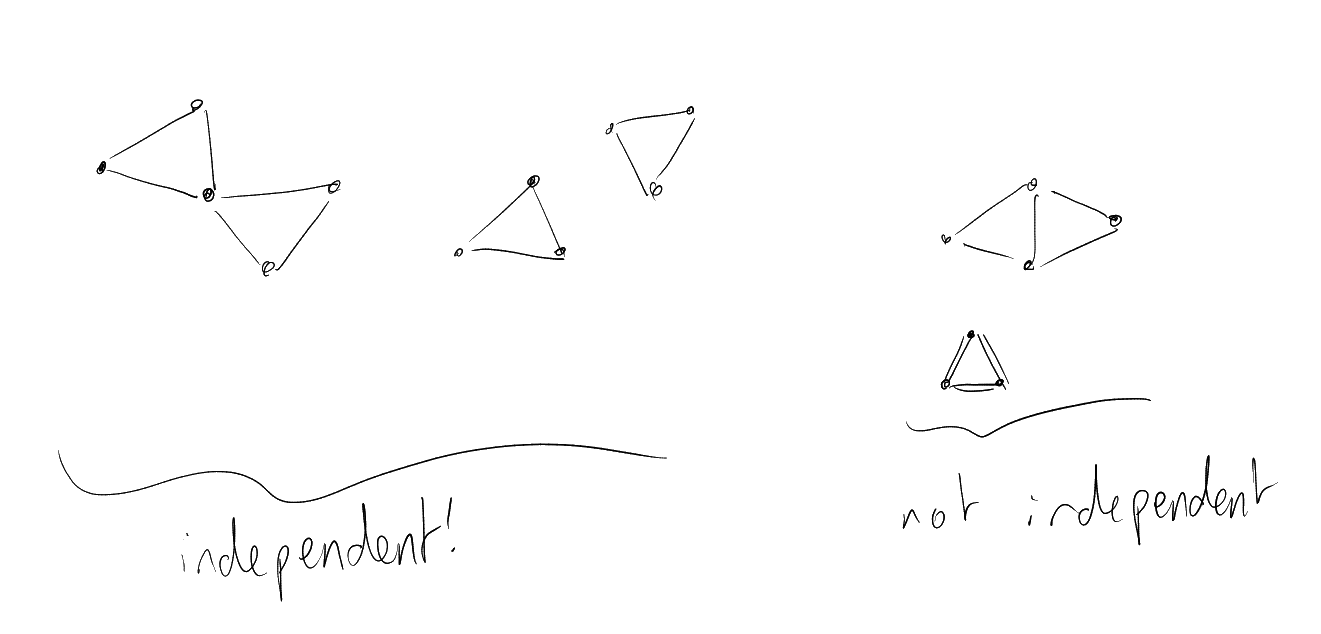

Definition 2.4 (Independence number).

Let

be a graph. Then

is independent if

in

for all .

Let .

Note.

To prove Theorem 2.3, we are trying to construct a triangle free graph on

vertices

with .

Lemma 2.5.

Assuming that:

Then

with probability tending to

as

(known as “with high probability (w.h.p.)”).

Remark.

We actually have

in this lemma.

Proof.

Let ,

for some .

Let

be the random variable that counts the number of independent

sets in

. Using

,

𝟙

by plugging in .

So by Markov,

We have a method for bounding the probability that

is large: Markov

says that .

What about bounding the probability that it is small?

Fact: Let be a

random variable with ,

finite. Then

for all ,

Reminder:

|

|

Lemma 2.6.

Assuming that:

Then |

|

with high probability.

Proof.

Let

be the random variable counting the number of triangles in

. Note

Mean is straightforward:

Variance is a little more tricky. First:

|

𝟙 |

We can write

Since the pairs of events are independent whenever

, and

since is

impossible, we have

Now note

Recall: In Lemma 2.5 we showed that for ,

, we

have

with high probability.

Proof of Theorem 2.3, a lower bound on .

Set ,

. Let

and let

be

with a vertex deleted from

each triangle. Then clearly ,

so with high probability we have

We also have with high probability:

So with high probability ()

and () hold (if

()

holds with

probability at least and

()

holds with probability at

least , then the probability that

they both hold is at least ).

So there must exist a graph

on vertices with no triangles

and independence number .

□

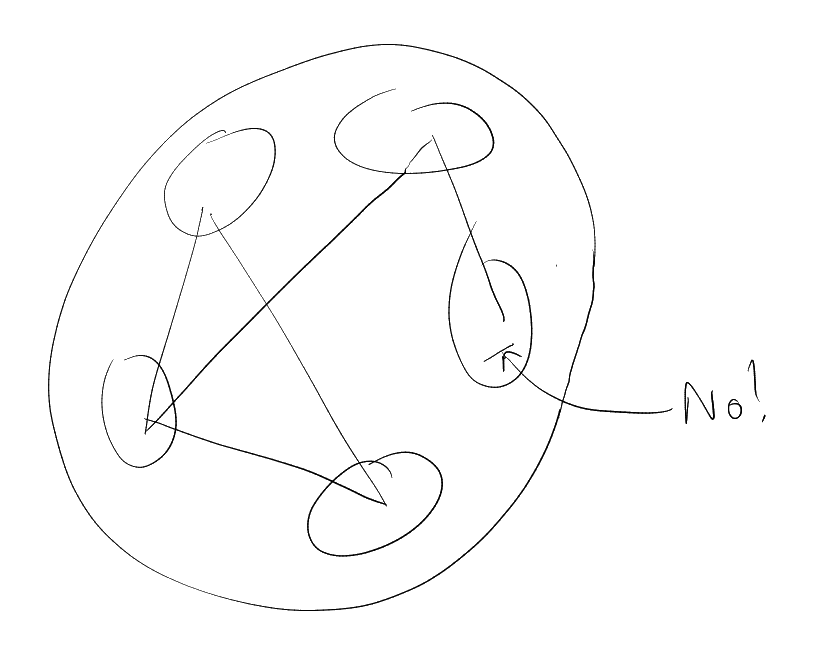

Definition (Chromatic number).

Let

be a graph. The chromatic number of

is the minimum such

that there exists

such that no edge has both ends in the same colour.

denotes

the chromatic number.

Definition 2.7 (Girth).

The girth of a graph

is the length of the shortest cycle in .

Using a method similar to the proof of Theorem 2.3 that we just saw, Erdős proved:

Theorem (Erdős).

There exist graphs

with arbitrarily large chromatic number and arbitrarily large girth, i.e. for all

there exists

with

girth

and .

This theorem is somewhat surprising, because if you think of examples of graphs

with large chromatic number, the first things you try have small girth (for example,

). It

shows that the answer to the question “what kind of necessary conditions are there for chromatic number to

be large?” is not so simple.