6 Dependent Random Choice

Definition 6.1 (-rich).

Let be a graph.

Say that is

-rich if for

every

we have

Theorem 6.2 (Dependent Random Choice).

Assuming that:

Then there exists

,

which

is

-rich.

Note that

doesn’t appear in the conclusion. It is a parameter that we can tune appropriately in applications.

Proof.

We sample

uniformly at random (with replacement). Then

𝟙

Let be the random variable

that counts the number of

with

We want

to be not too big. This will be the case (on average) because

is an increasing

function of

(so our probability distribution is biased away from fully selecting tuples that will increase

). We

make this precise as follows:

Note

|

𝟙 |

so

To finish, define to

be with a vertex

deleted from each

with . By

definition, is

-rich, so we now just

need to ensure that

holds for some choice of .

Indeed,

The last line follows from the assumption. □

Definition 6.3 (Extremal number).

Let

be a graph. The extremal numbers of

are

|

|

Theorem 6.4 (Erdős-Stone).

Assuming that:

Then |

|

Definition 6.5 (Complete bipartite graph).

is the complete bipartite graph with parts of sizes ,

respectively.

If , then for

all , we have

. More generally, a

complete -partite graph

will not contain a copy of .

Erdős-Stone says that these constructions are optimal, up to

edges.

Erdős-Stone doesn’t help us when .

In this case, it is true that

|

|

See Part II Graph Theory for proofs of both bounds.

These bounds are essentially the best known for .

We now prove a generalisation of this upper bound that holds for graphs other than complete bipartite

graphs:

Theorem 6.6 (Füredi).

Assuming that:

Then

for some

( depends

only on and

not on ).

Lemma 6.7.

Assuming that:

Then .

Proof.

First inject .

We now inductively place the vertices .

Assume we have embedded

into .

To embed ,

simply consider the .

These have been embedded inside of

and thus have

common neighbours. So there must be a choice for

that does not clash with the previous choices. □

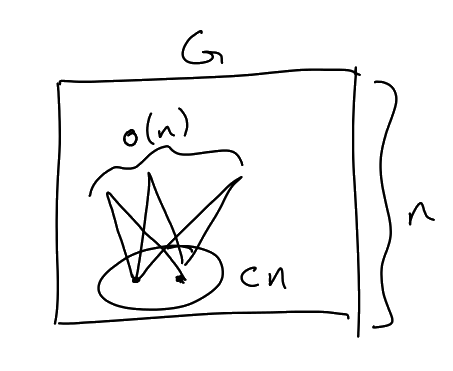

Proof of Füredi.

We are given

with . We choose

, and will show

. By lemma, enough

to find a -rich

set of size .

Let and

.

Then

as desired. □

Definition 6.8 (Hypercube graph).

denotes the hypercube graph: the graph with

and

are adjacent if they differ in exactly one coordinate.

Proof.

Let

and let be a

colouring of . Let

be the graph of the majority

colour. So . So we apply Dependent

Random Choice to find a -rich

set of size .

If ,

then

Then finish by applying Lemma 6.7.

The reasoning for choosing

is that we wanted to make

win against the . Setting

makes the powers of

cancel, but then we are

still left with the big

term, so instead we make

a bit bigger than .

□

Remark.

One can use this proof to get

Burr-Erdős conjectured that .

State of the art:

by Tikhomirov 2023.

Say I have a graph ,

with max degree

where fixed

and .

Then it is known that

Proposition 6.10.

Assuming that:

So Dependent Random Choice and Lemma 6.7 are enough to prove an upper bound that is almost linear in

, but not quite powerful enough

to prove the linear bound as in ().

Remark.

To improve this to get the bound ,

one idea might be to find a -rich

set where

(), where the

rich set has size

on

vertices. But this is impossible.

Proposition 6.11.

For all ,

there exists a graph

with edges so that

every set of size

contains some

with

common neighbours.

So we have to go back into the guts of the embedding idea. In some sense, the embedding algorithm was a little bit wasteful: for

example, we dumped

into the rich set without any clever choice.

The key idea to improve the previous bound will be to perform a more clever embedding algorithm that

requires a weaker notion of rich set. We want to use a weaker notion of rich set so that we can find large

linear size rich sets.

Definition 6.12 (Approximately -rich).

Let be a

graph. Say is

approximately -rich

if

|

|

Here we use the notation

|

|

Lemma 6.13.

Assuming that:

Then .

Lemma 6.14.

Assuming that:

Theorem 6.15 (Fox, Sudakov, Conlon).

Assuming that:

Remark.

This also improves our bound on :

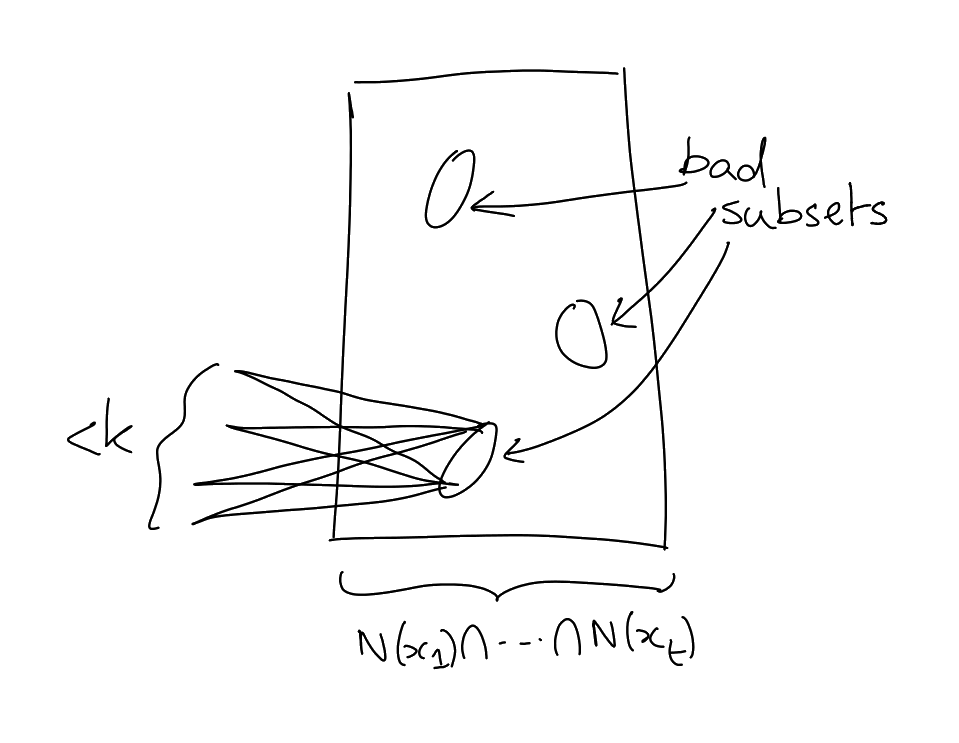

The key difference in proving Lemma 6.13 compared to the previous embedding algorithm is that we will need to embed

in a more clever way. We will

need to ensure that for all , the

neighbourhood of is not sent to

one of the bad subsets of (the

“bad” subsets are those which have

common neighbours).

Proof of Lemma 6.13.

For ,

, let

|

|

Say that is

healthy if

|

|

We will embed vertices of

one after the other. We will use this notion of healthiness to make sure that every time we place a

vertex, we keep plenty of good extensions.

Observation: If

is healthy, then the number of

such that

is not healthy is .

Proof of observation: Note

|

|

Let .

Then

But if , I

contradict that

is healthy. So we have proved the observation.

We now inject inductively.

Assume we have embedded

so far. We assume that we have

is healthy for all .

We now embed . Let

be the neighbour

of . We know

are healthy, so there are

at most (by observation)

ways of choosing

so that one of the neighbours becomes unhealthy. But there are only

neighbourhoods. So there

are choices that maintain all

healthy neighbours. Since ,

I can map

to a new vertex.

We now inject

exactly as we saw in the proof of Lemma 6.7. □

Proof of Lemma 6.14.

Let

be chosen uniformly at random. Let .

Let .

We have .

Let .

. Now

note that by Jensen,

|

|

So there is a

such that

So .

|

|

Theorem 6.16 (Graham, Rödl, Ruciński).

Assuming that:

Then there exists a constant

depending only on

,

such that

We will show

for some absolute constant .

Remark.

There exists

such that ,

for .

This is also “almost” the best bound known on these Ramsey numbers. The best known bound is

which was proved by Fox, Conlon, Sudakov.

Definition 6.17 ((p,eps)-dense).

Say that a graph

on

vertices

is -dense

if ,

, we

have

Lemma 6.18 (Embedding lemma for -dense graphs).

Assuming that:

Then .

Sketch of how to use embedding lemma: Apply lots of times, with say

. Get

lots of parts, with high density between all. Then can just greedily embed.

The lemma for greedily embedding will be:

Lemma 6.19.

Assuming that:

Then .

With the statements of these lemmas, we can already get an idea of where the

comes from. We will use

, so by Embedding lemma for

-dense graphs, we can always

either find a copy of , or zoom in

by a factor of to get a very dense

bipartite graph. We will apply this

times to get a highly dense graph, which we can then apply Lemma 6.19 to, and so we will need at least

vertices.

We now focus on discussing and proving Embedding lemma for

-dense

graphs.

Observation: Let

be a -dense

graph, and let

with and

. Then there

exists

such that

for all .

Proof.

Let .

Note

Hence

for all .

So we must have

Proof of Embedding lemma for -dense graphs.

The idea of the proof is to embed the vertices one by one. This could go wrong if we place vertices in

a way that reduces the possibilities for future vertices by too much. We avoid this issue by embedding

each vertex using the above Observation, to make sure that future vertices still have lots of valid places

to be embedded into.

Let . We

inductively map ,

. At each stage we maintain a

set of candidates for each .

In particular,

|

|

meaning after we have embedded ,

…, , we maintain that

after embedding

we have

We also require

where .

Say at step ,

I have mapped

preserving adjacencies and preserving ()

and ().

We now choose . We

want to choose .

Note

Let and

note

Now apply the observation with

and , where

, to find a

vertex

such that

as desired. □

Proof of Lemma 6.19.

Greedily embed

into . This is possible,

because when we embed ,

there are at least

many possible options (a lot!). □

Lemma 6.20.

Assuming that:

-

,

-

a graph with no

-dense

subgraph on

vertices

Then there exists

with

and

We will apply this Lemma with

and , so that we

get a subgraph

satisfying the assumptions of the greedy embedding algorithm (Lemma 6.19).

Proof.

We work by induction on .

For :

trivial, can just take ,

since .

Assume holds for .

Let

such that

where ,

because

is not -dense.

If then

let , so

|

|

Throw away vertices of degree

and we delete at most

of .

Call the resulting set ,

which is our desired set.

So we can assume that .

So we work with

and .

Fact: If I have a bipartite graph

with bipartition

and , then

there exists

with so

that

for all .

Proof: Let

chosen uniformly at random. Then

|

|

So if we let

be the set of vertices satisfying the desired condition, then we have

as desired.

Using this fact, we put

Let be

such that

and .

Now apply induction inside of

to find

with

and

Now consider the bipartite graph between

and .

Note

So apply fact to find

with and

. Now apply

induction inside of

to get

satisfying the induction hypothesis.

Set . We now check the max

degree condition. Let and

without loss of generality assume .

|

|

Then

as desired. □

This proof had some lies. At the end, we actually need to perform another step where we delete high degree

vertices. Also, for some of the inequalities, we treated them as equality so that we can divide by them nicely.

This can be fixed by passing down to a subgraph, because an average subgraph has the same density as the

original graph.

The proof is probably simpler if we instead make our inductive claim be about the density of

, and

then delete high degree vertices at the end to get a maximum degree condition.