Vector Calculus

February 4, 2022

Contents

1

Curves

1

1.1

Differentiating

the Curve . . . . .

1

Introduction

We will learn to differentiate and

integrate functions (or maps) of

the form

f :

m

n

R

→

R

|{z}

|{z}

domain

codomain

An element of

m

n

R

or R is a vec-

tor so this subject is called vector

calculus.

Examples of Maps

1. A function f :

n

R → R

defines a curve in

n

R . In

physics, we might think of

n

R as time and R

as phys-

ical space and write this as

f : t 7→ x(t)

with x ∈

n

R . (Obviously

we should take n = 3).

Generalising, a map

f :

2

n

R → R

defines a surface in

n

R , and

so on.

2. In

other

applications,

the domain

m

R

might be

viewed as physical space.

For example, in physics a

scalar field is a map

f :

3

R → R

for example temperature

T (x) is a scalar field, as is

the Higgs field.

A vector field is a map

f :

3

3

R

→

R

|{z}

|{z}

physical space

somethinge more abstract

for example the electric

field E(x) and magnetic

field B(x) are vector fields.

1

Curves

We consider maps of the form

f :

n

R → R

Assign a coordinate t to R and

use Cartesian coordinates on

n

R .

x = (x1, . . . , xn) = xiei

where ei is an orthonormal basis

such that ei · ej = δij. Note that

summation convention is used

here. (For

3

R

we also use nota-

tion {ei} = {ˆ

x, ˆ

y, ˆ

z}.)

The image of of the function f is

a parametrised curve x(t), with t

the parameter.

Examples

1. Consider the map

3

R → R

given by

x(t) = (at, bt2, 0)

The

curve

C

is

the

parabola a2y = bx2 in the

plane z = 0.

y

x

z

Note. When plotting

the curve, we lose in-

formation about the

parameter t.

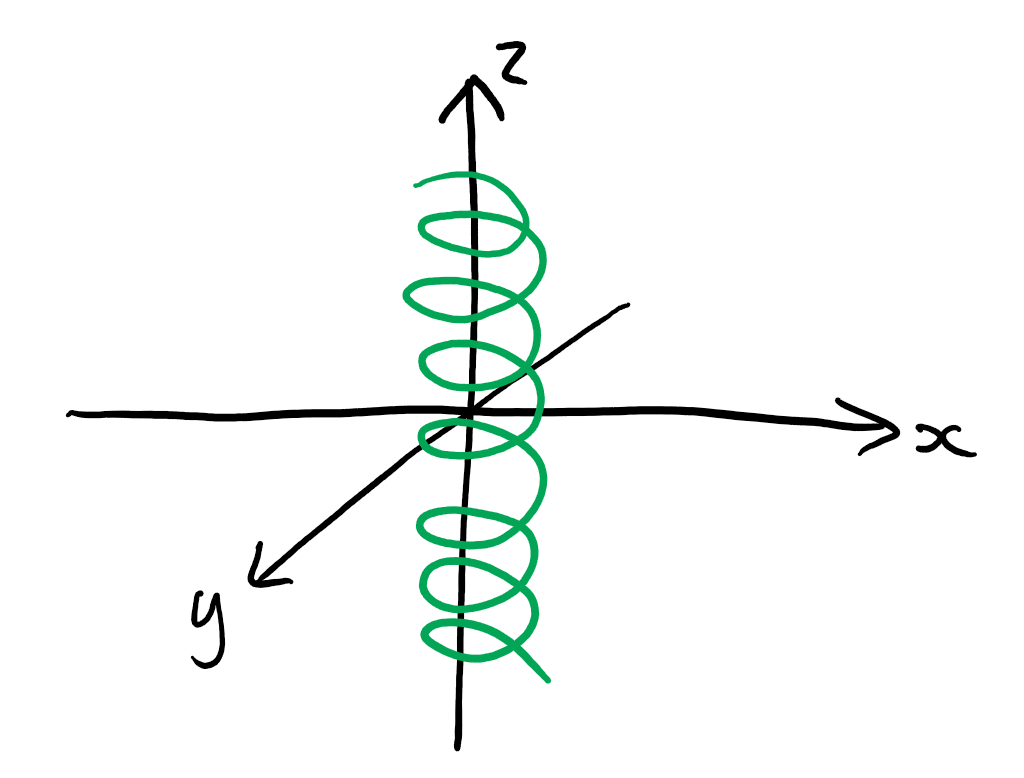

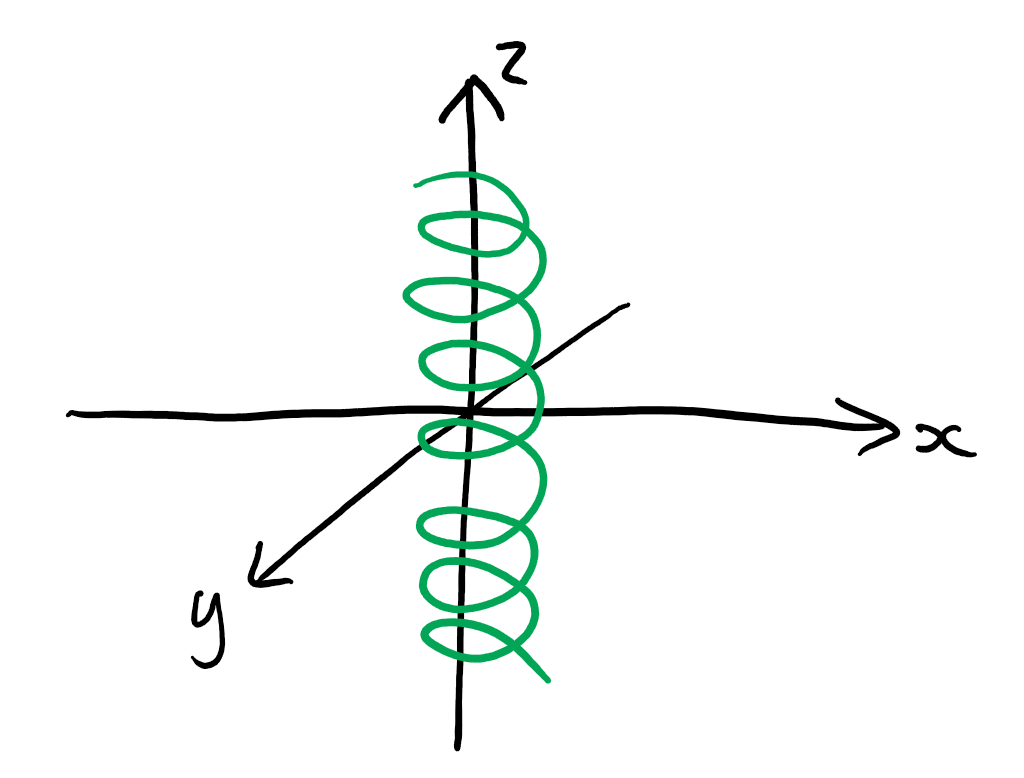

2. Consider

x(t)

=

(cos t, sin t, t)

The curve C is a helix.

The choice of parametrisation is

not unique, for example consider

x(t) = (cos λt, sin λt, λt).

This gives the same helix for all

λ ∈ R \ {0}.

Sometimes

the

choice

of

parametrisation

matters,

for

example if t is time and x(t)

is position, then the velocity

is proportional to λ.

But we

will see that some questions are

independent of the choice of

parametrisation.

1.1

Differentiating the

Curve

A vector function x(t) is differen-

tiable of t if, as δt → 0, we have

x(t+δt)−x(t) =

˙

x(t)δ(t)+O(δt2).

If

˙x(t)

exists

everywhere,

the

curve

is

said

to

be

smooth.

Note. “Big O” notation

O(δt2) means terms propor-

tional to δt2 or smaller.

In physics, dot is usually used

for time derivatives, for example

˙x(t) and prime for spatial deriva-

tives, for example f ′(x).

In maths, these are used inter-

changeably.

Some notation: we write

δx(t) = x(t + δt) − x(t)

The derivative is then

dx

δx

x ≡

:= lim

.

dt

δt→0 δt

Document Outline